LinkedIn’s Great, But …

LinkedIn’s Great, But …

Please let me start by saying the LinkedIn is a great platform, and has become a great place to create and sustain business contacts, but there’s a few things I’d like to highlight.

I write this article perhaps as a pointer for LinkedIn to start a journey which Facebook is on. Recently, I’ve mainly moved by blogs away from the site, as, in an instance, if you are too popular, they will take away all your articles, contacts, and you then have to wait for around three days for them even to respond to you. For customer support, they are not top on everyone’s list.

Usability on consent needs to be fair

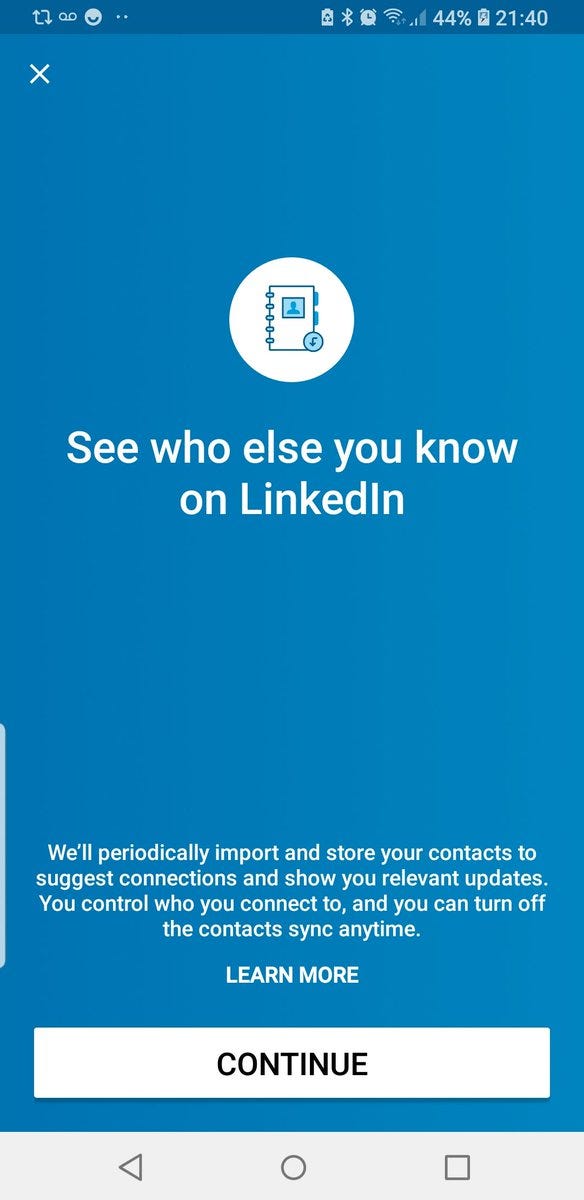

My first piece of advice to them is that they really need to learn a bit about the user, and know when they don’t want things — and not to rely on a menu setting buried in the settings page. On the left hand side of this text is a screen I continually get on my mobile device. This typically happens after I post something, and I often nearly click “CONTINUE”. But this is not a confirmation screen for my posting, it is the consent to dive into my contacts list, and harvest them, and then send them a message to ask to connect to me. I clicked on it by mistake once, and a close relatively asked why I wanted to connect to them on LinkedIn.

On a mobile device you just don’t have the space to go and setup your settings, but the worse thing about this screen is that the positive action is “CONTINUE” with a large white button where you normally look. And there’s no cancel button. Look up at the top, right-hand side, and you will see an ‘x’ — that is the cancel option. They have borrowed a method from Microsoft Windows, and which doesn’t work on mobile devices. For most users, they will click through, and never click on “LEARN MORE” (which shouldn’t be in upper case anyway).

I’d say:

- Don’t ask for consent through mobile devices, as they are not really designed to allow users to click-away or read.

- Be fair on the user’s preference, and make sure that the default is “No!”.

- Learn about the user, and stop pestering them.

- Colour code differences in messages.

- Try not to follow up on consent on the back of other things.

Tinder for Business People

LinkedIn, recently, too flashed up a message on mobile devices which asked for the users consent to be able to scan for contacts that were in your vicinity, and make matches. Basically whenever you met people in meetings, LinkedIn could be scanning for them, and finding out who you were meeting with. And so your phone became a listening beacon, reaching out to everyone you came in contact with.

Luckily, it looks like the bad press on the scanning meant that LinkedIn dropped the “Tinder for Business People” method [here].

A few years ago, this harvesting of data was quite common place, but after the Cambridge Analytica scandal and with the advent of GDPR, it’s not acceptable any more.

The Invisible Man

On 10 March 2017, for a few days, I became an invisible man:

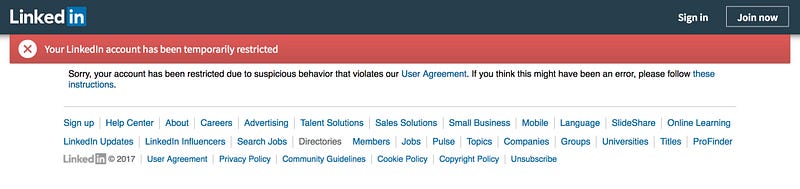

It all started on a Saturday when I received a message of:

and where all of my articles just disappeared from the Internet, and no-one could contact me on LinkedIn. There was no way of even logging into my account and backing up my articles.

I even tried to load the Google cache versions of my posts (as I need to access these for a forthcoming presentation), but these just redirected to a generic holding page on the LinkedIn site. It was a strange feeling, where all the articles that I had written, and which I often used in order to recover information from the past, had just disappeared. It really made me feel that I had no ownership of the content I’d created — and indeed this is the case.

So had I upset a government official on my viewpoints on cryptography? Was it a nation-state plot on my viewpoints on banning tunnels? Without any communication on the reason, I could only imagine what had caused the restriction.

So after three days of sending many emails to LinkedIn I received a message:

and I felt much better. The rights of academics to critical appraise things on the Internet is still alive and well, and it was all just an error.

As far as I can tell LinkedIn doesn’t like you to be too active, and if too many people click on your profile, it can cause a lock-out. This is because, I think, that LinkedIn thinks you have been spamming, even if you are not a spammer. So, if lots of people find your article interesting, it can cause too much activity, and there can be a lock-out on the account.

If this is the case, they really should tell you the reason why the restriction has been applied.

For advice here, get more staff to respond to customer requests, and especially telephone support. Also, revisit your security controls, and get them to be a little more intelligent.

Conclusions

As I said, LinkedIn’s great, but it needs to be careful when it comes to consent, and be fair on users. I think it is also falling behind on the editor to create articles, and then to be able to maintain them. If they want the platform to become a business blogging site, then they need to create tools to allow an improved editing experience and for their to be a way to find and maintain these blogs. There are occasions that I find it difficult to edit content after it has been published. I have other observations, but will leave them for private presentations.

And watch that you don’t become too popular, and you might become unpopular all of a sudden!