Quality Trumps Quantity in Research Papers?

Quality Trumps Quantity in Research Papers?

In my tips for a great PhD thesis [here] I define:

Quality is better than quantity. Some of the best thesis’ I read have been relatively short and sharp, but where the quality is high. A good eye for moving material in appendices is important and helps the examiner. For some reason, candidates like to produce a thick thesis, and they think that the more pages there, the better the material. This is often the opposite, and a thesis written with self-contained papers for chapters — which link together — are often the best in their presentation.

Some of the best PhD thesis’ I read have been less than 120 pages long, and some of the worst ones are often the ones that just go on and on, covering things which are completely irrelevant for the key contribution. Less is best is sometimes better, and quality is much better than quantity.

And so have research publications become a big game that academia play, and where everyone just follows a given formula? As a student you quickly learn that the peer review process involves packing in the references, defining your contribution, and then spend a good deal of time showing that you have put in some work to make the paper look good. A paper littered with typos and bad grammar, too, is unlikely to go anywhere.

I love the old “classic” papers which basically just outlined a new method and didn’t give you endless numbers of references. One of my favourite papers is by Fiat and Shamir [here][method]:

The chances of this getting through the review process now are probably low, as it has very few references and one of them is to the author’s work:

But it is the defining paper for Zero-knowledge Proofs.

Many people think that undergraduate degrees are unlikely to create ideas that are ground breaking, but it is often not the case. Ralph Merkle, in 1974, pitched the idea of public key encryption to his Professor in a coursework definition, and defined a method of key exchange (known as Merkle’s Puzzles). It was rejected by professors, and was finally resurrected when Ralph heard of the work of Martin Hellman and Whitfield Diffie at Stanford. The text below says:

Project 2 looks more reasonable maybe because your description of Project 1 is muddled terribly

Ralph then submitted his idea as a paper to the Communications of the ACM, but was rejected, as his paper did not have a formal literature review or references to other work. For Ralph he reasoned that there couldn’t have been references as there was no other work like this around. The paper was accepted three years later, but this time it has references to other work.

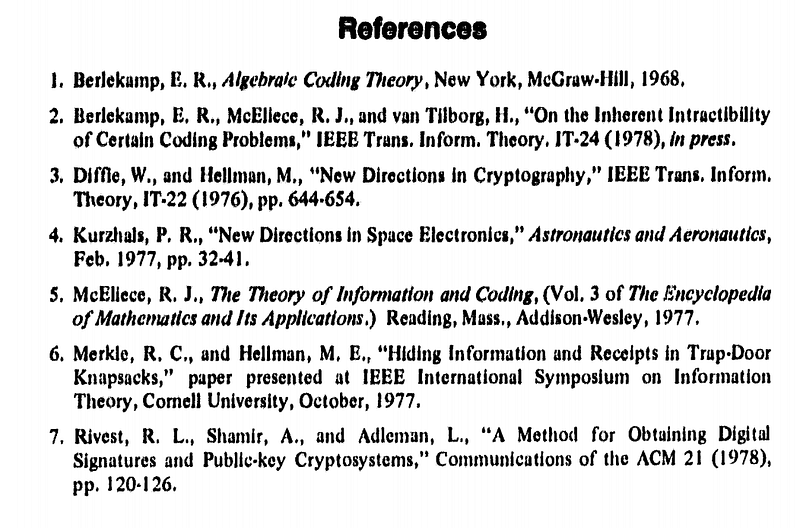

In a lesson for any modern researcher, in just two pages, Robert McEliece, in 1978, outlined the McEliece cryptosystem [paper][method]. Overall it is asymmetric encryption method (with a public key and a private key), and, at the time, looked to be a serious contender. Unfortunately for the method, RSA became the King of the Hill, and the McEliece method was pushed to the end of the queue for designers.

With ever inflated abstracts and references, the paper just seems to cover what it needs to with just a few passing references to some classic papers:

It has basically drifted in the 38 years since. But, as an era of quantum computers is dawning, it is now being considered as it is immune to attacks using Shor’s algorithm. In this page, I’ve avoided going into detail on the actual method, but have provided the code for you to test it out.

Conclusions

Reviewers are often busy people, and if a paper doesn’t fit the normal template of what makes a good paper, they will reject it (it’s an easy option for them).

If you are interested here is my first publication. It was published in a symposium related to education and the teaching of electromagnetic fields, and had just two pages, and was typed on a typewriter: