Can We Have Core Principles for Scottish e-Government and e-Health?

Can We Have Core Principles for Scottish e-Government and e-Health?

I’ve been reading up on the way that countries have transformed their health and social care infrastructures. At the core of this is strong leadership and vision provided from the top. Strong cybersecurity also plays a strong role is this, too. Those countries who succeed have often transformed their economies through digital innovation, also enhance the lives of their citizens.

The UK does not have a good track record with large-scale IT projects, and where an investment in Connecting for Health was cancelled after an investment of over £15 billion. Scotland, too, invested over £10 million into the development of systems around the Named Persons Act, and which few people actually know how the system would actually work. In the UK and Scotland, closed systems — developed by large companies — have not been a success. The meaningful digital interaction between the UK/Scottish governments and their citizens is minimal at its best, and almost non-existent in most places.

So while other countries in the world advance their electronic infrastructure for government and health care services, the UK and Scotland stay stuck without a proper identity system — and this is not a citizen ID system — and with little in the way of interaction between the government and its citizens. Why? Perhaps because there is generally a resistance to change, and little in the way of defining a road map and a vision.

So why doesn’t the Scottish Government define a set of principles that follow Estonia, and set a deadline of 2022 for its implementation? Here are the core principles of the Estonian system:

- Secure authentication — of all users with ID-card or mobile ID.

- Digital signing or stamping — of all health documents.

- Maximum transparency and accountability — actions will leave an unchangeable, secure trail.

- Cording of personal data — separating personal data from medical data.

- Encrypted databases — that removes the confidentiality risks.

- Monitoring — of all actions together with corresponding counter-measures.

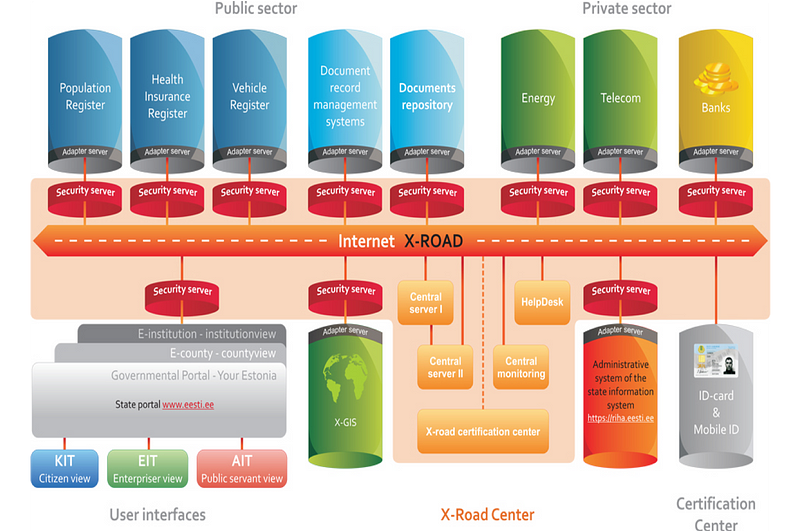

A core part of Estonian infrastructure is the X-road (Figure 1). X-Road is an integration layer that allows all public (and some private) databases to interact, making integrated digital services possible. Institutions are not locked into any one type of database or software provider. Databases are decentralised — every government agency or business can choose the software/hardware product that is right for them. All of the Estonian e-solutions that use multiple databases use X-Road. All outgoing data from the X-road is digitally signed and encrypted. All incoming data is authenticated and logged. National ID cards are mandatory in Estonia, giving digital access to all of Estonia’s secure digital services. The embedded chip on the card uses 2048-bit public key encryption, making it a secure and definitive proof of ID in an e-environment.

The integration has generally fitted in with the X-Road architecture, and then followed through with the integration of key elements of health and social care data:

Kalvet [1] defines that success of e-governance services in Estonia has a good deal to do with importance within public procurement for innovation. This avoided building on legacy infrastructures, and built a supportive environment for ‘ethical hackers’. Solvak et al [2] found that the adoption rate of e-service grows faster and peak adoption rate increases as user age decreases.

Metsallik et al [3] define the key lessons learnt from building the health care infrastructure as:

- Physicians and other professionals must change the way they fill out medical files to some extent — the trend is towards more uniform language.

- Semantic interoperability of medical data is hard to achieve.

- Data quality and secondary usage of data is still challenging.

- General acceptance of hospital personnel to share medical data in patient portal with patient is problematic.

- Much attention must be paid to the security and electronic authentication of the users.

- User interface development must not be underestimated.

- Medical data is not what people are looking for — they are interested in services.

Conclusions

Here’s a collection of do’s and do not’s:

- Do — Create a decentralised, distributed system so that all existing components can be linked and new ones can be added, no matter what platform they use.

- Don’t — Try to force everyone to use a centralized database or system, which won’t meet their needs and will be seen as a burden rather than a benefit.

- Do — Be a smart purchaser, buying the most appropriate systems developed by the private sector.

- Don’t — Waste millions contracting large, slow development projects that result in inflexible systems.

- Do — Find systems that are already working, allowing for faster implementation.

- Don’t — Rely on pie-in-the-sky solutions that take time to develop and may not work.

We need action, some vision and an architecture. We need to get citizens on our side, and build up their trust, and not build systems behind information firewalls. Let’s build a 21st Century infrastructure for our next generation. We need a massive investment in not only in people, but in technology, and must not give the funding to large and faceless companies.

References

[1] T. Kalvet, “Innovation: a factor explaining e-government success in estonia,” Electronic Government, an International Journal, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 142–157, 2012.

[2] M. Solvak, T. Unt, D. Rozgonjuk, A. Võrk, M. Veskimäe, and K. Vassil, “E-governance diffusion: Population level e-service adoption rates and usage patterns,” Telematics and Informatics, vol. 36, pp. 39–54, 2019.

[3] J. Metsallik, P. Ross, D. Draheim, and G. Piho, “Ten years of the e-health system in estonia.”

Notes:

This article is based on a forthcoming research paper published by Chaloner Chute and William J Buchanan.