When It Come Down To It, Cybersecurity Is All About Understanding Risk

When It Come Down To It, Cybersecurity Is All About Understanding Risk

Get two risk management experts in a room, one financial and the other IT, and they will NOT be able to discuss risk.

Go on … ask your CEO why your company has a VPN … and what the core threat is that it guards against, and how likely it is to happen? If they can answer these questions well, then stop reading this article, as you probably don’t have a problem in your company when it comes to cybersecurity. If the answer is “VPN stands for Virtual Private Network. That’s all I know about it. I have technical people who know about that kind of thing!”, then read on.

I have the privilege of advising organisations on cybersecurity, but I increasingly realise that there is a wide gap between the business elements of an organisation and those in technical roles. In a recent meeting I attended, the buzz words flew around with little care of their usage, and in the end, I didn’t really understand what the basic threat was. My conclusion was that the organisation just needed to sit down and work out a number of use cases for each of the major threats: insider fraud; large-scale data; major outage; etc, and then work out the likelihood of these, and, if possible, put a financial cost against them. Then they just had to work out if they just needed some insurance against the threats, or whether they could mitigate against them. For every use case, they needed a playbook of “What If …” scenarios, and make sure that they could cope with these.

Threats, risks, vulnerabilities and exploits

As humans we are driven by risks, and where we are continually weighing-up costs and benefits. Our lives are full of risks and threats. A threat is the actual thing that could actually cause harm, loss or damage, and a risk is the likelihood of this threat occurring. As humans, we take these things on, and continually weight things up, for ourselves, or for others. Those who succeed in their lives are often those people who can best understand threats and assess risks. IBM is one company who have managed to succeed within the computer industry for over 100 years. In that time they have continually been faced with new threats from competitors and from the rise of new technology, and each time they have generally managed to understand the risks that they face. In the 1960s, IBM has a lead in the market place for mainframe computers, but the 1970s saw the rise of the microprocessor and the personal computer (PC). And so IBM addressed this by adopting the rise of the PC, and eventually leading with their own standard. As the development of the personal computer quickened, again they found their leadership under threat, and decided to concentrate on high-end workstations and mainframe computers.

In our lives, too, we expose ourselves with vulnerabilities, and which are our weaknesses, and which could be exploited by others. Within Cyber intelligence we must thus need to continually understand our threats and vulnerabilities, and weigh up the risks involved. We have finite budgets for computer security, and thus must focus on those things which will bring benefit to an organisation. A major challenge is always to carefully define costs and benefits. A CEO might not want to invest in a new firewall if the justification is that it will increase the throughput of traffic. Whereas a justification around the costs of a data breach and an associated loss of brand reputation might be more acceptable.

Threat analysis is growing field and involves understanding the risks to the business, how likely they are to happen, and their likely cost to the business. Figure 1 shows a plot of cost against the likelihood, where a risk with a likely likelihood, and low costs, is likely to be worth defending against. Risks which are not very likely, and which have a low cost, and also a risk which has a high cost, but is highly likely, are less likely to be defended against. At the extreme, a high risk which has a low likelihood and which has high costs to mitigate against is probably not worth defending against. The probabilities of the risks can be analysed using previous experience or from standard insurance risk tables. Figure 2 outlines an example of this.

A lack of a communication

The major problem in defining risk and in implementing security policies is that there is often a lack of communication on security between business analysts and IT professionals, as they both tend to look at risk in different ways. Woloch [1] highlights this with:

“Get two risk management experts in a room, one financial and the other IT, and they will NOT be able to discuss risk. Each puts risk into a different context … different vocabularies, definitions, metrics, processes and standards …“

At the core of Cyber intelligence is that a formalisation of the methodology used to understand and quantify risks. One system for this is CORAS (A Framework for Risk Analysis of Security Critical Systems) and which has been developed to try and understand the risks involved. A key factor of the framework is to develop an ontology (as illustrated in Figure 3) where everyone speaks using the same terms. For example: A THREAT may exploit a VULNERABILITY of an ASSET in the TARGET OF INTEREST in a certain CONTEXT, or a THREAT may exploit a VULNERABILITY opens for a RISK which contains a LIKELIHOOD of an UNWANTED INCIDENT. In this way, all of those in an organisation, no matter their role, will use the same terminology in describing threats, risks and vulnerabilities.

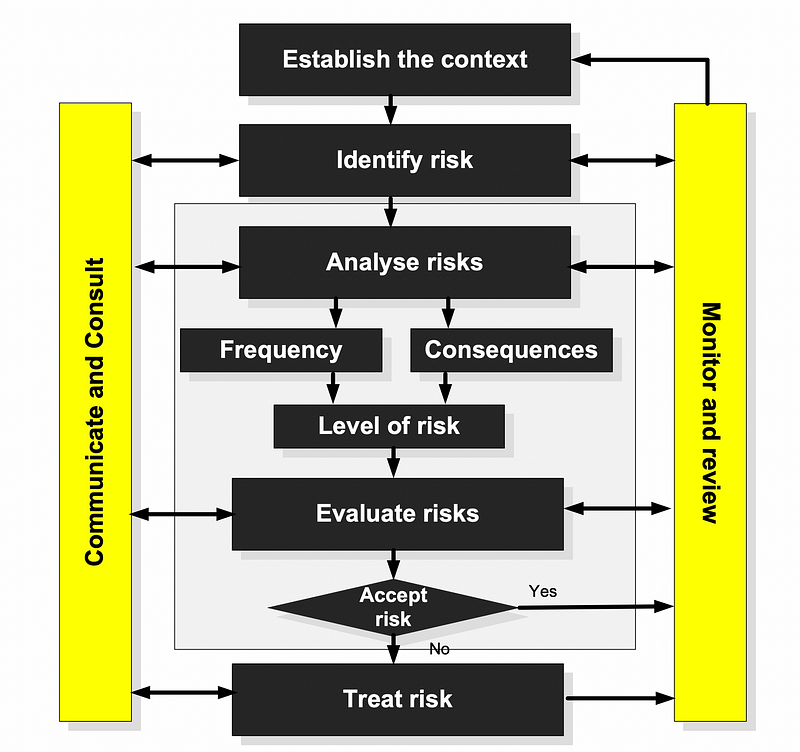

For risk management, it is understood that not all threats can be mitigated against, and they must thus be managed. Figure 4 shows the methodology used by CORAS in managing risks, where a risk might be accepted if the cost to mitigate against it is too high. Network sensors can thus then be setup to try and detect potential threats, and deal with them as they occur. For risk avoidance, systems are setup so that a threat does not actually occur on the network. An example of risk management is where a company might not setup their firewalls to block a denial-of-service (DoS) attack, as it might actually block legitimate users/services, and could thus install network sensors (such as for Intrusion Detection Systems) to detect when a DoS occurs. With risk avoidance, the company might install network devices which make it impossible for a DoS attack to occur.

The importance of clearing defining threats allows us to articulate both the threat itself, and also define clearly the entities involved with an incident. Figure 5 shows an example of defining the taxonomy used within a security incident, and where A [Threat] is achieved with [Attack Tools] for [Vulnerabilities] with [Results] for given [Objectives].

Conclusions

Why has a company like IBM survived over 100 years, and how has Microsoft managed to sustain itself as a leader in its field for over 40 years? They both understand threats to their organisation, and are able to mitigate against them. If you want to learn more on the methods that can be used for Cyber Intelligence, then watch out for our new book (expected release date around Oct/Nov 2019):

References

[1] Woloch, B. (2006). New dynamic threats requires new thinking–“Moving beyond compliance”. Computer Law & Security Review, 22(2), 150–156.