The Wonderful World of Bob and Alice: Martin Gardner, ARS, NSA Interference, and Cracking Knapsack

The Wonderful World of Bob and Alice: Martin Gardner, ARS, NSA Interference, and Cracking Knapsack

And atomic weapons and cryptography are covered by special secrecy laws

We have been very fortunate with our Applied Cryptography and Trust module, and where several world leaders in cryptography have given up their own time to come along and chat with our students. This week it was Len Adleman — Turing Prize winner and co-creator of the first public key encryption method (RSA).

Rump sessions

Along the way, we talked about the crazy rump sessions of the cryptograph conferences held in Santa Barbera. He is Crypto 1981, and you can see classic papers from Len, Adi Shamir, Marty Hellman and Manual Blum (Len’s mentor):

and from Whitfield Diffie and David Chaum:

For example, Manual Blum presented his coin flipping method [here], and which has been referenced over 1,000 times in other research work:

The end of the 1970s and 1980s basically laid down the foundation for the security of the Internet. We may take it for granted, but the work undertaken at that time brought forward public key encryption research, along with areas of digital signing, hashing, Zero Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs), and so many other areas.

One of the greatest inventions of the 20th Century: RSA

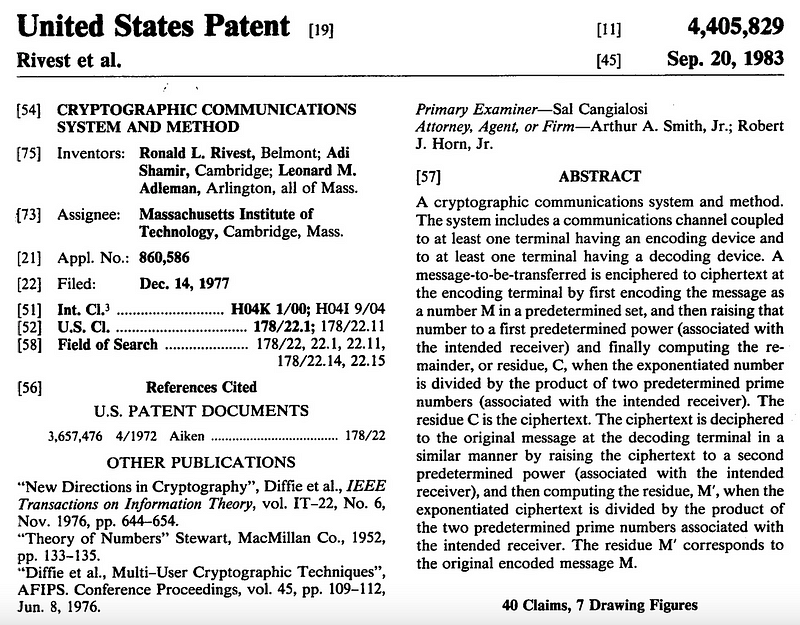

And for his part in the creation of the RSA method, he was told, “You are going to make a lot of money”, so Len went out and bought himself a red Toyota. For Len, too, the protection of RSA with a patent provided to be a key element in protecting their amazing invention. It has assigned to MIT was a key strategic decision, and MIT had the power to defend against mighty companies who may want to pick the method apart:

And, did you know that the patent has an identifier of 4,405,829 and which is a prime number? In a few pages, the patent brings the RSA method alive:

and they even gave a nice simple example:

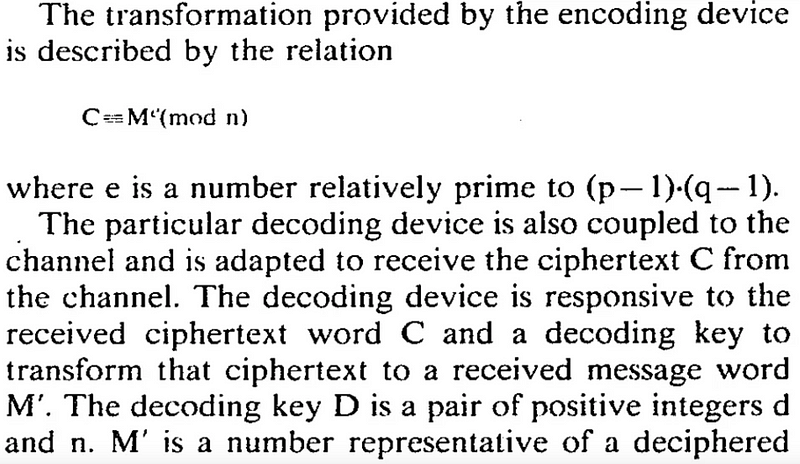

At the core of RSA was an amazing team — and each part played their role perfectly. I was a great friendship with Ron (Rivest) being the great thinker of new ideas, Adi (Shamir) as the cracker of ideas, and Len (Adleman) providing the theoretical backbone.

Martin Gardner’s column

And, so, Len tells the tale about how famous he became with the publication of Martin Gardner’s article in Scientific American:

In order to explain the RSA concept, Martin’s provided a background of the Diffie-Hellman method for which he outlined:

Then in 1975 a new kind of cipher was proposed that radically altered the situation by supplying a new definition of “unbreakable.” a definition that comes from the branch of computer science known as complexity theory. These new ciphers are not absolutely unbreakable in the sense of the one-time pad. but in practice they are unbreakable in a much stronger sense than any cipher previously designed for widespread use. In principle these new ciphers can be broken. but only by computer programs that run for millions of years!

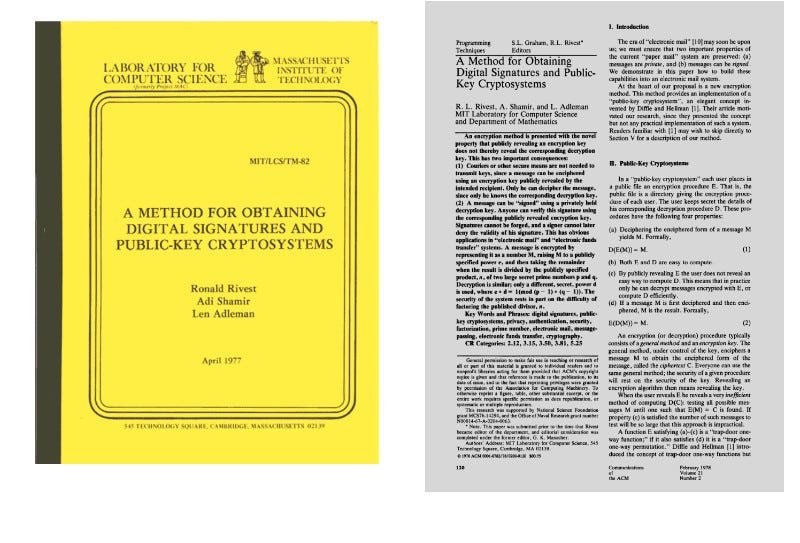

With the RSA method, Martin Gardner outlined:

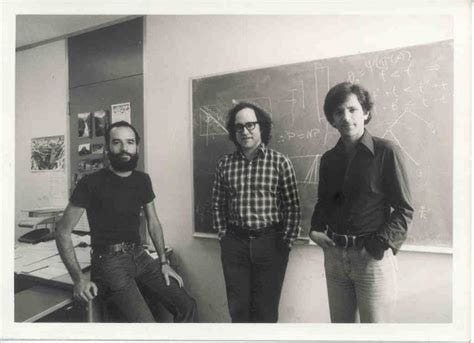

Their work supported by grants from the NSF and the Office of Naval Research. appears in On Digital Signatures and Public-Key Cryptosystems (Technical Memo 82. April. 1977) issued by the Laboratory for Computer Science Massachusetts Institute of Technology 545 Technology Square. Cambridge Mass. 02139.

The memorandum is free to anyone who writes Rivest at the above address enclosing a self-addressed. 9-by-12-inch clasp.

On receipt the requesters eventually (it took over four months in many cases) received a precious piece of history:

It seems unbelievable these days, but the original methods were based on two 63-digital prime numbers that would be multiplied to create a 126-digit value:

Contrast this with the difficulty of finding the two prime factors of a 125- or 126-digit number obtained by multiplying two 63-digit primes. If the best algorithm known and the fastest of today’s computers were used, Rivest estimates that the running time required would be about 40 quadrillion years’

A 256-bit number, at its maximum, generates 78-digits [here]:

115,792,089,237,316,195,423,570,985,008,687,907,853,269,984,665, 640,564,039,457,584,007,913,129,639,936

The 40 quadrillion years have not quite happened, and where 512-bit keys are easily broken in Cloud. If you are interested, here is a 512-bit integer value which has 148 digits, such as [example]:

13,407,807,929,942,597,099,574,024,998,205,846,127,479,365,820,5 92,393,377,723,561,443,721,764,030,073,546,976,801,874,298,166,9 03,427,690,031,858,186,486,050,853,753,882,811,946,569,946,433,6 49,006,084,096

The search for prime numbers, too, has been progressive since 1977, and by 2014, the world discovered a 17,425,170-digit prime number. The finding of prime numbers makes the finding of them in the RSA method must easier.

No Such Agency

But, some people didn’t like this public key encryption and thought that it breached US embargoes on the provision of military-grade material. And, so, the NSA (“No Such Agency”) tried to put some pressure on Rivest, Shamir, and Adleman to not publish their invention. But, it was too late, and many of the papers had gone out — “with students outside Ron’s office, stuffing thousands of stamped addressed letters with the paper”. The genie was out of the bottle, and no one could not put a stopper on it.

Once Martin had published the article, the requests for the article came rushing in, especially as the paper had not yet appeared in the Communication of the ACM. Initially, there were 4,000 requests for the paper (which rose to 7,000), and it took until December 1977 for them to be posted.

Why did it take so long to get the paper published and also to send them out?

Well the RSA method caused significant problems within the US defence agencies. This was highlighted in a letter sent from J.A.Meyer to the IEEE Information Theory Group on a viewpoint that cryptography could be violating the 1954 Munitions Control Act, the Arms Export Control Act, and the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), and could thus be viewed equivalent to nuclear weapons. In even went on to say:

Atomic weapons and cryptography are also covered by special secrecy laws

The main focus of the letter was that any work related to cryptography would have to be cleared by the NSA before publication. In fact, the letter itself had been written by Joseph A Meyer, an employee of the NSA.

Joseph had already been embroiled in controversy with a proposal to fit a tracking device to the 20 million US citizens who had been associated with crime. The tag would then be used to monitor the location of the “subscriber”, and to detect when they broke a curfew or committed a crime. In this modern era of GPS tracking of everyone’s phones, Joseph’s dream has actually become a reality, but now everyone is monitored.

The RSA team thus had a major dilemma, as many of the requests for the paper come from outside the US. Martin Hellman, who was a co-author of the Diffie-Hellman method, had already had problems with ITAR and even decided to present the paper himself in 1977 at Cornell University rather than the practice of letting his PhD students present the work.

His thinking was that the court case would be lengthy and that it would damage his PhD student’s studies (Ralph Merkle and Steve Pohlig), and so he stood up for academic freedoms. Initially, the students wanted to present their work, but their families did not think it a good idea. Eventually, though, Ralph and Steve stood beside Hellman on the stage to present the paper but did not utter a word.

With this stance, the cryptographers held ground and hoped that a stated exemption on published work within ITAR would see them through. The worry, though, did delay the paper being published, and the posting of the article. In reply to Meyer’s letter, the IEEE stood its ground on their publications being free of export licence controls, with the burden of permissions placed on the authors:

and then the additional response from the IEEE put in place safeguards for the publishing of material that did not have the correct level of permission:

The scope of the impact of RSA was perhaps not quite known at the time with Len Adleman stating:

I thought this would be the least important paper my name would ever appear on

In fact, Adleman has said that he did not want his name on the paper, as he had done little work on it, but he did insist that his name went last. Often papers, too, have an alphabet order, and if so the method could have been known as the ARS method … not the kind of thing that you would want to say to audiences on a regular basis.

Breaking Knapsack

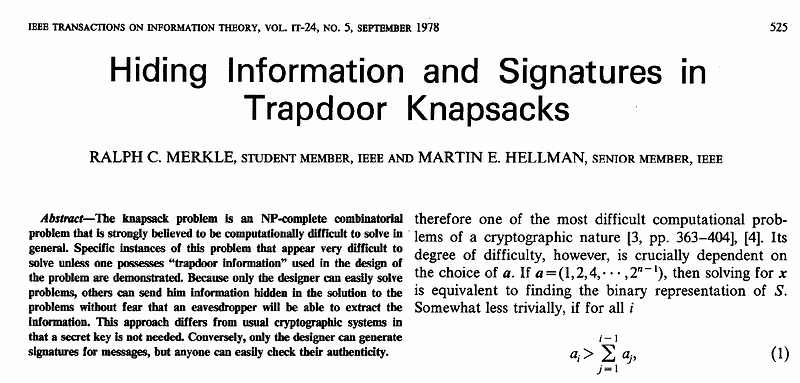

But, RSA was not the only show in town for public key encryption, and where Ralph Merkle and Marty Hellman had shown a Knapsack method:

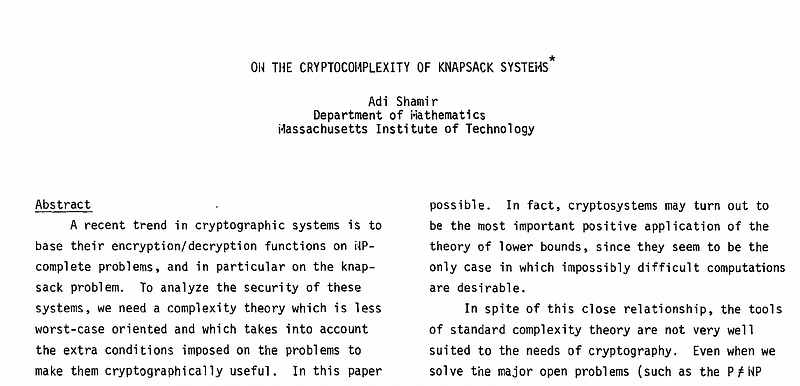

But, Adi Shamir came along and cracked it:

and for Len to then demonstrate it:

Len’s memory was giving a live demo of the crack on an Apple 2 computer at a Rump session, and of his worry that the computer was likely to crash on him.

Well, give it a listen:

If you want to find out more about RSA, try here: