Noyce, Moore and Grove — A Template for Spin-out/Start-up Success?

Noyce, Moore and Grove — A Template for Spin-out/Start-up Success?

The Harder I Practice, the Luckier I Get

So, is there a formula for a successful start-up/spin-out — and if you followed it, you would be guaranteed success? For this, many people approach me and say, “I want to have a spin-out. What should I do?”. To me, this is a little like saying, “I want to fly, can you give me wings?”. So, let me lay out a few things that I have learned over the past two decades of being involved in spin-out companies.

Overall, we have been very lucky in our spin-outs, with three highly successful ones, and where two have been bought out (Zonefox and Symphonic), and the third expanding fast within digital forensics (Cyacomb). But, as they say, “The Harder I Practice, the Luckier I Get”. We have had failures, but every time our team has licked their wounds and come back stronger. And the one thing, though, I’ve observed is that the leadership of an innovative company often needs to change as it evolves, and those leading it need to know when they need to move aside and let others take their place.

So, I’m going to define the three stages as: Visionary, Strategy and Grit, and where there are very different leaders at each stage. But, fundamentally, the first two stages set up the culture and approach of the company, and which are fundamental to its long-term beliefs and ideals. Overall, few companies in the third stage can turn their ship and travel in a different direction. The approach of IBM, for example, is still one of an engineering approach to their work and one built on rewarding innovation.

Forgive me, I’m technical

And, so I am a cryptography professor, and not a business one, so please forgive me for not covering the core literature in the areas of business. I am also highly technical, and that is what I love. I would never want to be a cut-throat business person and would never want to be. I love inventing things and seeing ideas grow from seeds. And one thing I know is when my role is complete as part of the innovation process and when to move aside.

But, deeply technical people are at the core of creating a successful spin-out, along with people with a vision. And, so, I would like to lay out a basic template of my observations in creating a successful spin-out — and based on the ones we have produced. To me, also, a great technical company should have a core of theoretical work, and where the best work can come from academic collaborations. In academia, there is an attention to detail and theory, and which makes sense of the complex world of invention and discovery. But, the magic comes from practical implements, and where the best collaborations mix practice with theory.

So, my basic template for success is to get the right leadership team in place, and get the right leader for the right time. A core part of this is knowing when the leader should move aside and let someone else take over. For this, I’ll map it to the success of Intel and its first three employees: Robert Noyce, Gordon Moore and Andy Grove.

Stage 1: Robert Noyce — the Visionary (1968–1975)

If there’s a superstar of our digital era, it must be Robert Noyce. Imagine inventing the one thing that now drives virtually everything in our digital age: the integrated circuit. It all started in the late 1950s with John Bardeen and Walter Brattain at Bell Labs and who first invented the transistor. William Shockley advanced the concept with the creation of the bipolar transistor. Bardeen and Brattain were a great research team and has a great balance of theoretical skills with practical ones. Brattain did the theory, and Bardeen did the practical work. All three eventually received a Nobel Prize for their work — with Brattain being one of the few people to ever get two Nobel Prizes.

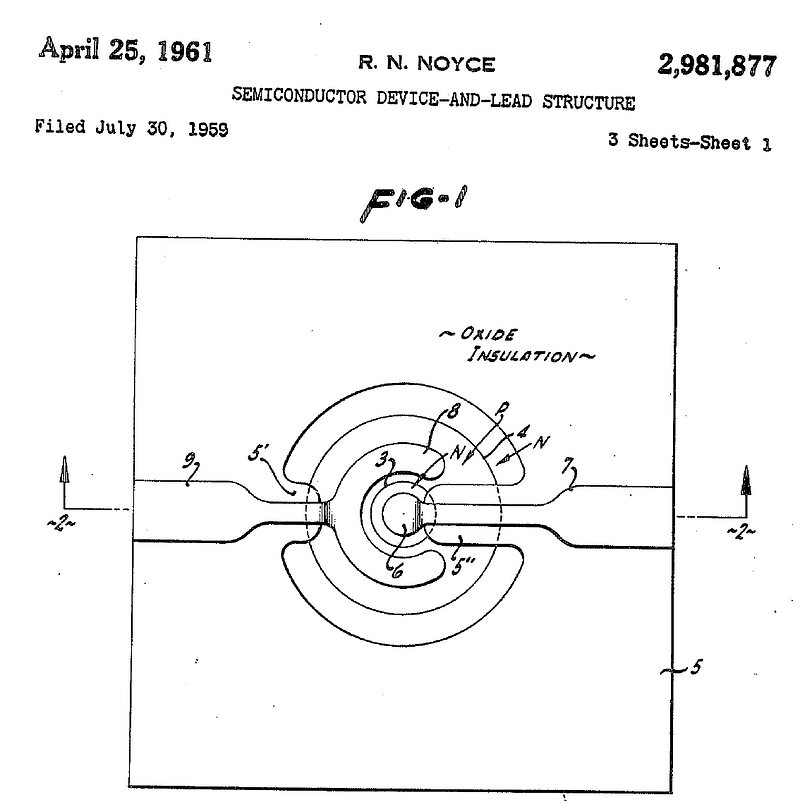

While Bell Labs was a hub of innovation at the time, Shockley wanted to take a good deal of the credit for the invention of the transistor and left Bell Labs to set up his own company in 1955: Shockley Semiconductor. For this, we recruited Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore to work on his ideas. But Shockley was a difficult boss and had an overbearing approach to his management style. This caused eight of Shockley’s employees — including Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore — to leave the company and start their own venture with the support of Fairchild Camera and Instrument. It was there, in 1961, that Robert created one of the most significant patents of all time:

It outlined a magical way of doping a semiconductor substrate and producing an integrated circuit:

This invention differed from Jack Kilby’s work at Texas Instruments, as Robert outlined a monolithic circuit while Jack defined a hybrid circuit approach. And, so, Fairchild grew fast as a leader in semiconductors, but as the company grew, Robert increasingly missed the days of true innovation and decided to team up with Gordon Moore to create Integrated Electronics (which would end up just being known as Intel).

And, so, Robert was the anchor for the creation of Intel. A true visionary and someone that people trusted and listened to. It was thus not difficult for Andy Rock to find the seed funding for the start-up — as it had Robert’s name on it. Those who invested in the company were not investing in the company and its projected product line but in Robert.

In Stage 1 we thus have the visionary leader. The person who can see beyond the near future and build a company that could scale towards their vision, and someone who both inspired people to believe and someone who others could trust with the vision.

And, so, Robert led Intel from 1968 to 1975 but knew the time that he needed to hand over to someone else. And, that needed to be someone who had a core understanding of the technology required to scale Intel: Gordon Moore.

Stage 2: Gordon Moore — the technical and strategic genius (1975–1987)

In Stage 2, we move from the visionary leader to the strategic leader, and there was no better person than Gordon Moore (and who created the mighty Moore’s Law — and which is still relevant to this day). Gordon had an eye for detail and quality. For Intel to succeed, they needed someone to convert the vision shown by Noyce to something that matched the market. For this, he invested heavily in R&D and made Intel a world leader in the memory market. But, he showed his strategic brilliance by spotting the opportunity to initiate work in microprocessors.

As we all know, in 1969, Intel was designing some chips for Busicom and decided to integrate these into a single device, which could be programmed with software. The designer was Ted Hoff, and he produced the first microprocessor: the 4004. And, so, as the memory market became crowded and profits fell, Gordon moved Intel out of it and ramped up the development of the 8-bit and 16-bit microprocessors. The device that sprang out of this development was the Intel 8086, which — luck would have it — was the processor selected for the IBM PC. It was luck and strategy, and Gordon was a core part of this. Most CEOs would have pushed forward in the memory market, but Gordon focused Intel’s R&D on new markets.

Gordon Moore was thus the second phase leader and the one who could stop opportunities and be in the right place at the right time to exploit them. Without his technical genius, the company would have struggled to understand how to scale R&D into emerging markets.

Stage 3: Andy Grove — the detail (1987–1998)

And now we need the last piece of the puzzle … Andy Grove. Intel had grown up as a company of idealists and lacked a “Us and Them” approach to management. Noyce, Moore and Grove had led the company, but they were colleagues. Many remember that it was often difficult to find Gordon in the company when they visited him, as he sat in a cubical in the open plan set up and shared the same physical space with others in the company. There were no fancy trimmings for Gordon in his CEO role — he was as much a worker as any other.

And both Robert and Gordon had a gentle approach to their management style, but Andy brought an edge that the congenial Moore and Noyce could never give.

At eight years old, Andy escaped with his mother from the Nazis and left Hungary at the age of 20 during the Hungarian Revolution. He arrived in the US as a refugee with no money but with a passion for learning. Eventually, he gained his PhD from the University of California, Berkeley.

And, so, Andy provided the grit and desire to succeed that Intel needed, and, as with Gordon, he had an eye for quality and in making sure that everything that Intel did was at the highest possible technical level.

And so it was Andy who had the grit to move Intel out of its core memory business and into microprocessors. He had a knack for taking complex problems and distilling them down into strategies that were easy for those involved to understand. Perhaps it was because he was an engineer first and then had to learn about management and strategic approaches.

His strategy was to move Intel out of memory and straight into the PC. The natural choice at the time for the processor in the PC was Motorola, but Grove managed to get the technical support in place for the Intel chip, and that allowed engineers to develop their prototypes. And, what did Grove do about the expertise in memory? He put it to good use in integrating SRAM caches into the processor, which massively speeded up their operation.

Andy thus had the grit that Intel required to take it into new markets and win:

The most important role of managers is to create an environment where people are passionately dedicated to winning in the marketplace. Fear plays a major role in creating and maintaining such passion. Fear of competition, fear of bankruptcy, fear of being wrong and fear of losing can all be powerful motivators.

Conclusions

Moore and Noyce drove Intel to become one of the world’s most powerful companies. The team had a perfect balance … Noyce inspired everyone he met and built an initial customer base, while Moore built technical excellence and then followed through. It was left to Grove to focus on detail and excellence. William Shockley failed in the market as he couldn’t share success with others, while Moore, Noyce and Grove built a culture of collaboration and in taking shared ownership of the company they built.

The first stages of a company are thus so important is building its culture into the future. If those involved in those first stages do not act in the right way, then the company may be doomed to have the wrong approaches to its employees and customers. The initial leaders are the ones that people should look up to and be inspired by. This is not often through business practice, but having core scientific and technical expertise in their field.

So, get your team in place … a visionary, a technical genius, and a true leader with grit. But, knowing the best leader at any given time and knowing when to hand over to someone else can take the next great step forward. And, go do something wonderful …

If you are interested, here are some of my tips for spin-outs: