A Soft Target: Are Higher Education Infrastructures At Risk?

A Soft Target: Are Higher Education Infrastructures At Risk?

The days of 9–5pm security support are gone … Higher Education Needs 24x7 SOC

They helped build the Internet

Academia was one of the first infrastructures to build and use the Internet — in fact, they build ARPANET and which morphed into the Internet. And so, you will find that they often have privileged IP address ranges, such as for Class A or Class B. With this, when IPv4 address ranges were initially given out, universities and research organisations were granted large address spaces to allocate to their growing networks. No one, at the time could have ever envisaged in how much the Internet has grown since then. To make things easy, nearly every computer that was allocated a public address could be connected to directly — these were routable Internet addresses. To overcome these direct connections, firewalls filtered data packets and tried to stop malicious access.

The Happy Phase of the Internet

We might call this the “Happy Phase” of the Internet, where it basically interconnected trusted organisations and where there was no real concept of many people outside this trust circle having access to a computer. It was a new frontier in technological development and seemed to be a nice way to send emails between academics and researchers and to showcase their latest research work.

By a public address, we have the concept that it is possible to route data directly to a computer. As you connect to this article, you are likely to be using a non-routable IP address, which is hidden between a NAT (Network Address Translation) router. These privileged academic address spaces supported public IP address spaces for thousands or even millions of hosts — and where a Class A IP address can allow over 16 million computers to have a public IP address.

The University of California, Berkley, for example, has an IP address and subnet of 104.247.81.71/8, and where 104.0.0.0 is the network address, and where 24 bits in the address can be used for subnetworks and hosts. This means that the host part can be used to create subnetworks with an extension of the subnet field. Ultimately, a Class A address can give up to 16,777,216 publicly addressable hosts. And, so, while most organisations put their computers in private address spaces (though NAT), universities had enough IP addresses to allow many computers to be publicly addressable.

In fact, at one time, an academic’s desktop computer was likely be allocated a public address and could thus be directly contacted. And, so, as long as the computer was powered on, it could be addressable. Along with this, a log of any sites visited would leave a trace of the public IP address. In fact, it was all too common to add a DNS entry of Bob’s computer as “Bob.uni.edu”. But, this was all created in a time of little concern about cybersecurity, and it allowed academic infrastructures to grow dynamically — and under their own control.

This was all set up before any real concept of requiring cybersecurity — as the networks were often just used to interconnect networks. So while other infrastructures have closed themselves to external threats, universities — in places — can still support legacy applications and have security support which ends after the working day.

24x7 Security Operations Centre

I have observed the rise of the SOC (Security Operations Centre) in the finance industry — in fact, many of our graduates go into jobs that relate to this. I’ve also toured many of the SOCs in Glasgow and Edinburgh and love to see the fusion of data from inside and outside the companies. Basically, these companies had to move from being a Monday to Friday, 9am-5pm company to looking after security 24x7.

But what about Higher Education (HE) as a sector? Well, I might be wrong, but higher education has not adopted the concept of 24x7 SOCs, and at 5 pm, many networked infrastructures hand over to support staff. There is very little in the way of sharing security resources across HE, too. Like it or not, our adversaries don’t work 9–5pm (GMT), and are most likely to be on a different time zone in the world.

And, so, we see the University of Manchester and the University of the West of Scotland (UWS) being subject to a cyber attack in the last few weeks, and this could be the start of a targeted offensive against network infrastructure with weaker support for security. The attack on the University of Manchester was part of a vulnerability around the usage of the MOVEIt protocol:

The MOVEit Transfer managed file transfer (MFT) software [here] has been developed by Ipswitch (and which is a…medium.com

Results

The attack on the UWS site happened around 6 July 2023, and now it is suspected data from the breach where it is reported that the ransomware gang of Rhysida [here] is selling breached data to the highest bidder for 20 bitcoins (£450,000):

The site went down for around a week, and it affected a range of internal systems. At the current time, it is thought that the breached data includes bank details and national insurance numbers, along with internal documents from the university. Presently, there is no real information on whether these documents are real or not.

The breach happened around the first week in July 2023, and when the UWS site started to show the message of:

At first sight, this could be a standard domain take-over, and where the HTTPs certificate is valid:

But, with a lookup, we see that the domain name has been parked at 3dqkz9i.x.incapdns.net:

% nslookup www.uws.ac.uk

Server: 8.8.8.8

Address: 8.8.8.8#53

Non-authoritative answer:

www.uws.ac.uk canonical name = 3dqkz9i.x.incapdns.net.

Name: 3dqkz9i.x.incapdns.net

Address: 107.154.112.136Overall, Incapsula is a cloud-based hosting company — it may be that the university is using the cloud provider for their hosting. Generally, it is not recommended to actually log into the site (even though the password hint is ‘Google’), as the main page seems to have a redirected site on the redirected site:

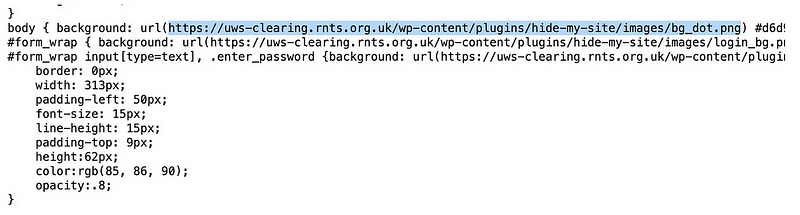

Generally, there is a sign of the usage of WordPress, and which may be used to deliver the UWS Web pages (wp-content is a typical folder used to store digital content on a Word Press site) — this might point to a WordPress site take-over:

If we go to the Way Back engine, the last recorded site archive was on 1 July [here]:

Overall, the HTML is there is signs of WordPress being used:

If we try some of the links above, we get:

Conclusions

Academic information infrastructures have grown independent of each other — and were a key part of building the Internet. Those, though, were the “nice” days, but where we have massively grown our digital footprint. The exposure is now massive, especially with the rise of SaaS, and where many universities use third-party applications for contacts and HR systems. We need to move into a world in which shared cybersecurity and setting up 24x7 SOCs for universities is a must … as it is for most other sectors.

I believe that university security teams should work together, and merge resources for defence, and bring in companies who are well used to running SOCs in the finance sector. At least, every institute should look at running SOC on the basis that we would see in the industry — as the data contained in the network — and the risk to student’s education — is too great a risk. To me, the University of Manchester and UWS data breaches are just the start of a targetted offensive against softer targets. And, the ability to recruit and keep cybersecurity staff in academia is going to be a major problem.