Few Remember The Beaten Finalists … Here’s The Mighty Serpent

Few Remember The Beaten Finalists … Here’s The Mighty Serpent

In 2000/2001, NIST ran a competition on the next-generation symmetric key method, and Rijndael won (and which was created by its Belgium creators: Vincent Rijmen and Joan Daemen). But in second place was Serpent, and which was created by Ross Anderson, Eli Biham, and Lars Knudsen. Let’s have a look at the competition, and then outline an implementation of Serpent in Go lang. In the end, it was the speed of Rijndael that won, over the enhanced security of Serpent. If NIST had seen security as more important, we might now be using Serpent than Rijndael for AES.

The competition

NIST created the race for AES (Advanced Encryption Standard). It would be a prize that the best in the industry would join, and the winner would virtually provide the core of the industry. So, in 1997, NIST announced the open challenge for a block cipher that could support 128-bit, 192-bit, and 256-bit encryption keys. The key evaluation factors were:

Security:

- They would rate the actual security of the method against the others submitted.

- This would method the entropy in the ciphertext — and show that it was random for a range of input data.

- The mathematical foundation of the method.

- A public evaluation of the methods, and associated attacks.

Cost:

- The method would provide a non-exclusive, royalty-free basis licence across the world;

- It would be computationally and memory efficient.

Algorithm and implementation characteristics:

- It would be flexible in its approach, and possibly offer different block sizes, key sizes, convertible into a stream cipher, and so on.

- Be ready for both hardware and software implementation, for a range of platforms.

- Be simple to implement.

Round 1

The call was issued on 12 Sept 1997 with a deadline of June 1998, and a range of leading industry players rushed to either create methods or polish down their existing ones. NIST announced the shortlist of candidates at a conference in August 1998, and which included some of the key leaders in the field such as Ron Rivest, Bruce Schneier, and Ross Anderson (University of Cambridge) [report]:

- Australia LOKI97 (Lawrie Brown, Josef Pieprzyk, Jennifer Seberry).

- Belgium RIJNDAEL (Joan Daemen, Vincent Rijmen).

- Canada: CAST-256 (Entrust Technologies, Inc), DEAL (Richard Outerbridge, Lars Knudsen).

- Costa Rica FROG (TecApro Internacional S.A.).

- France DFC (Centre National pour la Recherche Scientifique).

- Germany MAGENTA (Deutsche Telekom AG).

- Japan E2 (Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation)

- Korea CRYPTON (Future Systems, Inc.)

- USA: HPC (Rich Schroeppel), MARS IBM, RC6(TM) RSA Laboratories [try here], SAFER+ Cylink Corporation, TWOFISH (Bruce Schneier, John Kelsey, Doug Whiting, David Wagner, Chris Hall, Niels Ferguson) [try here].

- UK, Israel, Norway SERPENT (Ross Anderson, Eli Biham, Lars Knudsen).

One country, the USA, had five short-listed candidates, and Canada has two. The odds were thus on the USA to come through in the end and define the standard. The event, too, was a meeting of the stars of the industry. Ron Rivest outlined that RC6 was based on RC5 but highlighted its simplicity, speed, and security. Bruce Schneier outlined that TWOFISH had taken a performance-driven approach to its design, and Eli Biham outlined that SERPENT and taken an ultra-conservative philosophy for security, in order for it to be secure for decades.

Round 2

And so the second conference was arranged for 23 March 1999, after which, on 9 August 1999, the five AES finalists were announced:

- Belgium RIJNDAEL (Joan Daemen, Vincent Rijmen).

- USA: MARS IBM, RC6(TM) RSA Laboratories, TWOFISH (Bruce Schneier, John Kelsey, Doug Whiting, David Wagner, Chris Hall, Niels Ferguson)

- UK, Israel, Norway SERPENT (Ross Anderson, Eli Biham, Lars Knudsen).

- Canada: CAST-256 (Entrust Technologies, Inc),

The big hitters were now together in the final, and the money was on them winning through. Ron Rivest, Ross Anderson and Bruce Schiener all made it through, and with half of the candidates being sourced from the USA, the money was on MARS, TWOFISH or RC6 winning the coveted prize. While the UK and Canada had both had a strong track record in the field, it was the nation of Belgium that surprised some and had now pushed itself into the final [here].

While the other cryptography methods which tripped off the tongue, the RIJNDAEL (‘Rain-doll’) method took a bit of getting used to, with its name coming from the surnames of the creators: Vincent Rijmen and Joan Daemen.

Ron Rivest — the co-creator of RSA, had a long track record of producing industry-standard symmetric key methods, including RC2, and RC5, along with creating one of the most widely used stream cipher methods: RC4. His name was on standard hashing methods too, including MD2, MD4, MD5, and MD6. Bruce Schneier, too, was one of the stars of the industry, with a long track record of creating useful methods, including TWOFISH and BLOWFISH.

Final

After nearly two years of review, NIST opened up to comments on the method, which ran until May 2000. A number of submissions were taken, and the finalist seemed to be free from attacks, with only a few simplified method attacks being possible:

Table 1: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4863838/

As we can see in Table 1, the methods had different numbers of rounds: 16 (Twofish), 32 (Serpent), 10, 12, or 14 (Rijndael), 20 (RC6), and 16 (MARS). Rijndael had a different number of rounds for different key sizes, with 10 rounds for 128-bit keys and 14 for 256-bit keys. Its reduced number of rounds made it a strong candidate for being a winner.

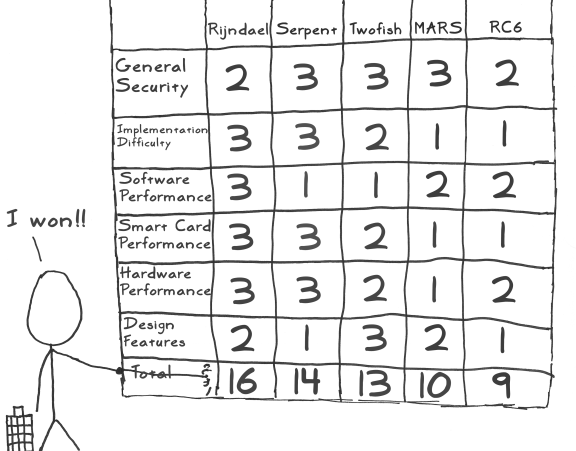

In the AES conference to decide the winner, Rijndael received 86 votes, Serpent got 59 votes, Twofish 31 votes, RC6 23 votes, and MARS 13 votes. Although Rijndael and Serpent were similar, and where both used S-boxes, Rijndael had fewer rounds and was faster, but Serpent had better security. The NIST scoring was:

Serpent

For many observers, Seperent pushed itself to be more secure and over-engineered with the number of rounds. The following is some sample code [here]:

namespace Serpent

{

using Org.BouncyCastle.Crypto;

using Org.BouncyCastle.Crypto.Engines;

using Org.BouncyCastle.Crypto.Modes;

using Org.BouncyCastle.Crypto.Paddings;

using Org.BouncyCastle.Crypto.Parameters;

using Org.BouncyCastle.Security;

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

var msg="Hello";

var iv="00112233445566778899AABBCCDDEEFF00";

var size=128;

var mode="ECB";

if (args.Length >0) msg=args[0];

if (args.Length >1) iv=args[1];

if (args.Length >2) size=Convert.ToInt32(args[2]);

if (args.Length >3) mode=args[3];

try {

var plainTextData=System.Text.Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(msg);

var cipher = new SerpentEngine();

byte[] nonce = new byte[8];

Array.Copy(Convert.FromHexString(iv), nonce, 8);

PaddedBufferedBlockCipher cipherMode = new PaddedBufferedBlockCipher(new EcbBlockCipher (cipher), new Pkcs7Padding());

if (mode=="CBC") cipherMode = new PaddedBufferedBlockCipher(new CbcBlockCipher(cipher), new Pkcs7Padding());

else if (mode=="CFB") cipherMode = new PaddedBufferedBlockCipher(new CfbBlockCipher (cipher,128 ), new Pkcs7Padding());

CipherKeyGenerator keyGen = new CipherKeyGenerator();

keyGen.Init(new KeyGenerationParameters(new SecureRandom(), size));

KeyParameter keyParam = keyGen.GenerateKeyParameter();

cipherMode.Init(true,keyParam);

int outputSize = cipherMode.GetOutputSize(plainTextData.Length);

byte[] cipherTextData = new byte[outputSize];

int result = cipherMode.ProcessBytes(plainTextData, 0, plainTextData.Length, cipherTextData, 0);

cipherMode.DoFinal(cipherTextData, result);

var rtn = cipherTextData;

// Decrypt

cipherMode.Init(false,keyParam);

outputSize = cipherMode.GetOutputSize(cipherTextData.Length);

plainTextData = new byte[outputSize];

result = cipherMode.ProcessBytes(cipherTextData, 0, cipherTextData.Length,plainTextData, 0);

cipherMode.DoFinal(plainTextData, result);

var pln=plainTextData;

Console.WriteLine("=== {0} ==",cipher.AlgorithmName);

Console.WriteLine("Message:\t\t{0}",msg);

Console.WriteLine("Block size:\t\t{0} bits",cipher.GetBlockSize()*8);

Console.WriteLine("Mode:\t\t\t{0}",mode);

Console.WriteLine("IV:\t\t\t{0}",iv);

Console.WriteLine("Key size:\t\t{0} bits",size);

Console.WriteLine("Key:\t\t\t{0} [{1}]",Convert.ToHexString(keyParam.GetKey()),Convert.ToBase64String(keyParam.GetKey()));

Console.WriteLine("\nCipher (hex):\t\t{0}",Convert.ToHexString(rtn));

Console.WriteLine("Cipher (Base64):\t{0}",Convert.ToBase64String(rtn));

Console.WriteLine("\nPlain:\t\t\t{0}",System.Text.Encoding.ASCII.GetString(pln).TrimEnd('\0'));

} catch (Exception e) {

Console.WriteLine("Error: {0}",e.Message);

}

}

}

}A sample run [here]:

=== Serpent ==

Message: Hello 123

Block size: 128 bits

Mode: ECB

IV: 00112233445566778899AABBCCDDEEFF00

Key size: 128 bits

Key: CD64EC39A109230E7F90A7D8C6E9E65E [zWTsOaEJIw5/kKfYxunmXg==]

Cipher (hex): 36D0182E84C2F6309194D65BDB670B0A

Cipher (Base64): NtAYLoTC9jCRlNZb22cLCg==

Plain: Hello 123Conclusions

The mighty Ross Anderson has contributed so much to cryptography, and Serpent was just one of these. Here is his work on Red Pike: